The following is a review of several events where I encountered artificial intelligence (AI) technology or engaged in technology discourse while conducting curatorial research in Berlin (This journal covers the events that happened from July to August 2023.)

Let’s start with AI: Ancestral Immediacies, Technologies of Making the Past Present (link), which took place at the end of July at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. This institution has recently undergone a change in direction due to a change in directorship. The three-day program examined AI technologies with a strong emphasis on temporality and intelligence connected to the past. In particular, as the title Ancestral suggests, it focuses on the multiple intelligences, technologies, rituals, and spiritualities that have accumulated over time.

The word Ancestral, which is often used as the mainstream Western art scene takes a more decolonizing turn, is not easy to translate into Korean. The literal translation would be Josang (ancestor) or Seonjo (forefather), but the English word does not connote the sense of “object to be subserved” that Korean gives. Thus, if you want to translate it as an object that refers to the people who lived before and their intelligence, I think you need a different paraphrase. Overall, the program was somewhat unfamiliar to Koreans, and I believe one of the reasons for this lies in the translation of the word Ancestral. The purpose of the program is to reflect on the intelligence and knowledge that the West has accumulated through different plural bodies. This purpose is also related to the O Quilombismo exhibition (link) that was held at HKW simultaneously. This is a decolonizing/post-colonization exhibition that actively introduces the cultures and struggles of the Global South, including Africa and South America. Looking at Ancestral from this perspective is very different from the Korean “Ancestral,” as it is an attempt to look again at cultures that have been the subject of plunder and extraction, and AI is also read within that extension.

Of course, this is not the only thing that is new in the Korean context. The exhibition actively addresses the tainted aspects of current AI technology, such as labor issues. However, it also focuses on the concept of “spiritual intelligence” to interpret and understand these issues. It encompasses non-technical perspectives, bringing immaterial uncertainties and other forms of unexplained intelligence and knowledge that humans have accumulated to the forefront in order to explain the current AI hype. In order to have the most effective conversations about AI (without losing a perspective on post-colonialism), they seemed to attempt to recognize the role of spiritual intelligence. Conversely, in the Korean tech scene, which has warmly embraced and integrated Western, especially American, technology and culture, the notions of ancestry and mind may appear somewhat unfamiliar. In particular, the idea that the body and mind are separate entities, which is emphasized in Western philosophy, is not widely accepted in Korea. Therefore, from a Korean perspective, this notion may seem somewhat idealized or romanticized, particularly considering that Koreans are known to be loyal supporters and enthusiastic users of AI technology.

Three weeks later, a performance of Shared Landscape (link), co-directed by Stefan Kaegi, known in Germany as the Rimini Protocol, and Caroline Barneaud of the Vidy-Lausanne Theater in Lausanne, Switzerland, took place.

Taking place in the forest of the Waldschule Hangelsberg, which is located about an hour from downtown Berlin, this outdoor, site-specific performance lasts approximately seven hours. The two directors happily leave their familiar territory, the theater, to discuss the environment and explore the ecological, sensory, and artistic aspects of our connection to it. As you wander through the forest, you will come across fragmented performances that are man-made landscapes created by various artists. You would hear a conversation between a farmer who drives a tractor and a behavioral ecologist. Performers hide in the forest and play sporadic sounds. You can lie down and listen to three-dimensional sounds created using binaural technology. A performer also projects his or her disabled body onto the current landscape.

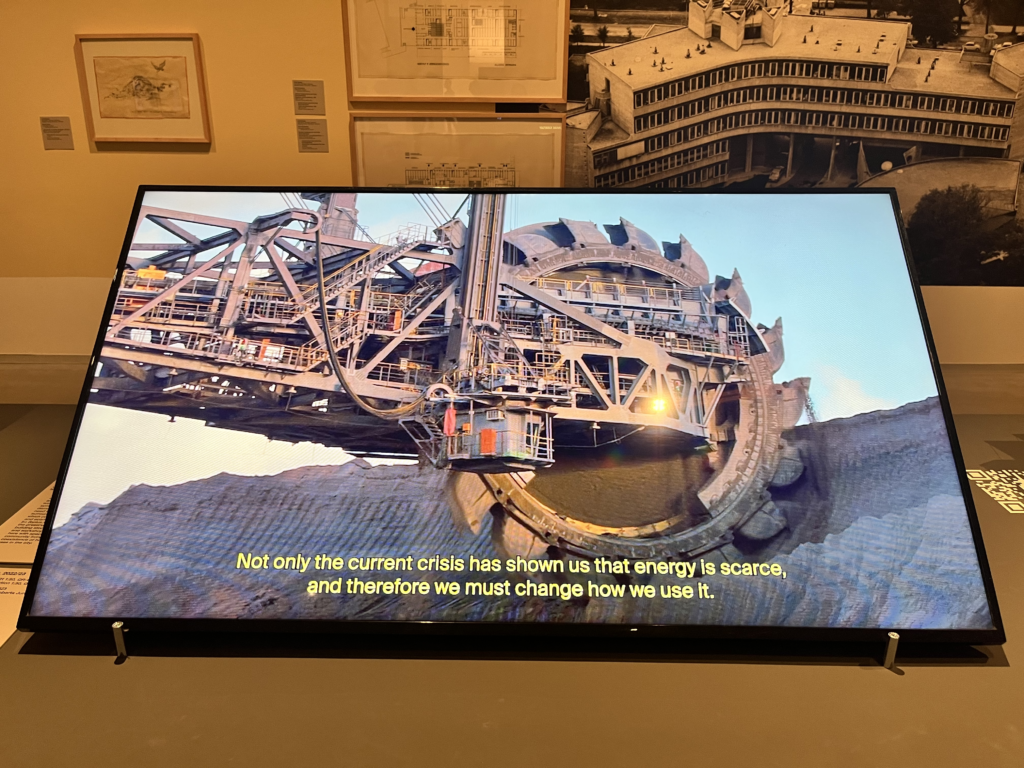

In this performance, which aims to provide a holistic experience of the environment and ecology, Begüm Erciyas & Daniel Kötter highlight a specific area where mining extraction is occurring. Using military videography techniques, they provide a viewpoint that can ascend vertically up to 25 meters from the audience’s current position in virtual reality (VR). The irony of technology is evident from start to finish. While the viewer is physically on the ground in the forest, (military) technology allows us to see a perspective that is inaccessible to humans. Like Google Satellite View, a bird’s-eye view creates a sense of expansiveness, of not knowing how far you can go. As the viewer slowly ascends vertically from their standing position, they experience a mix of anxiety and excitement. However, upon reaching the top of the forest, where the ground seems farther away than the sky, a sense of suffocation from the vastness of the landscape overwhelms any feeling of liberation. The technology featured in the performance is directly intertwined with the ecological landscape, presenting a landscape of technology that wanders between the two poles of contradiction.

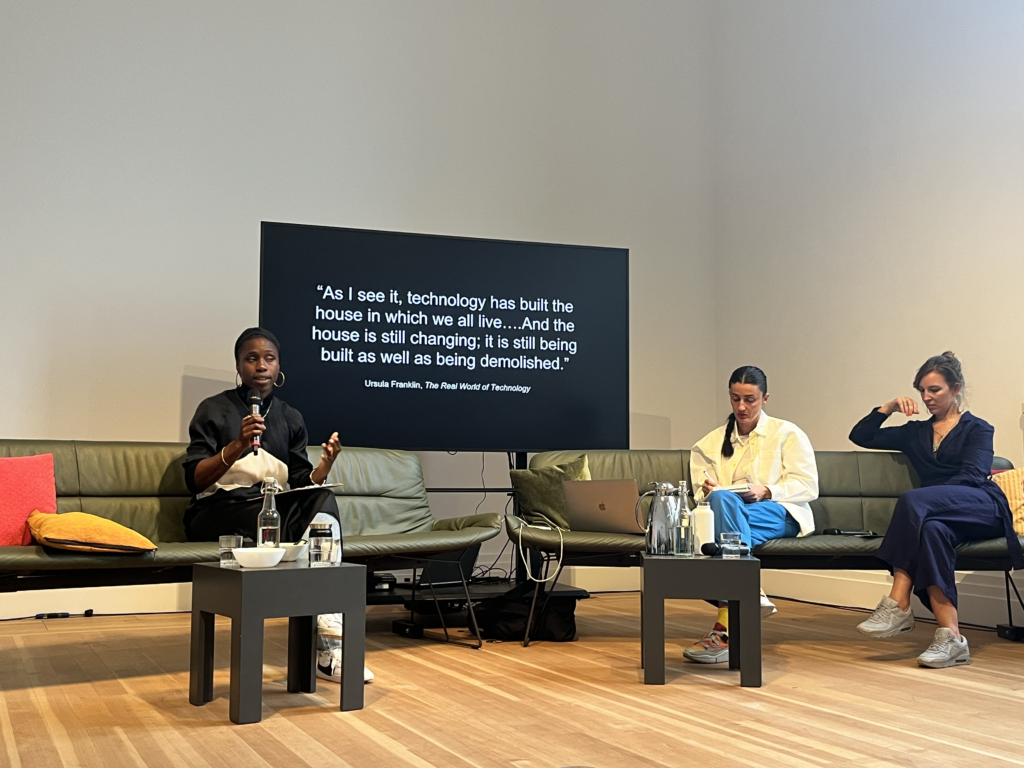

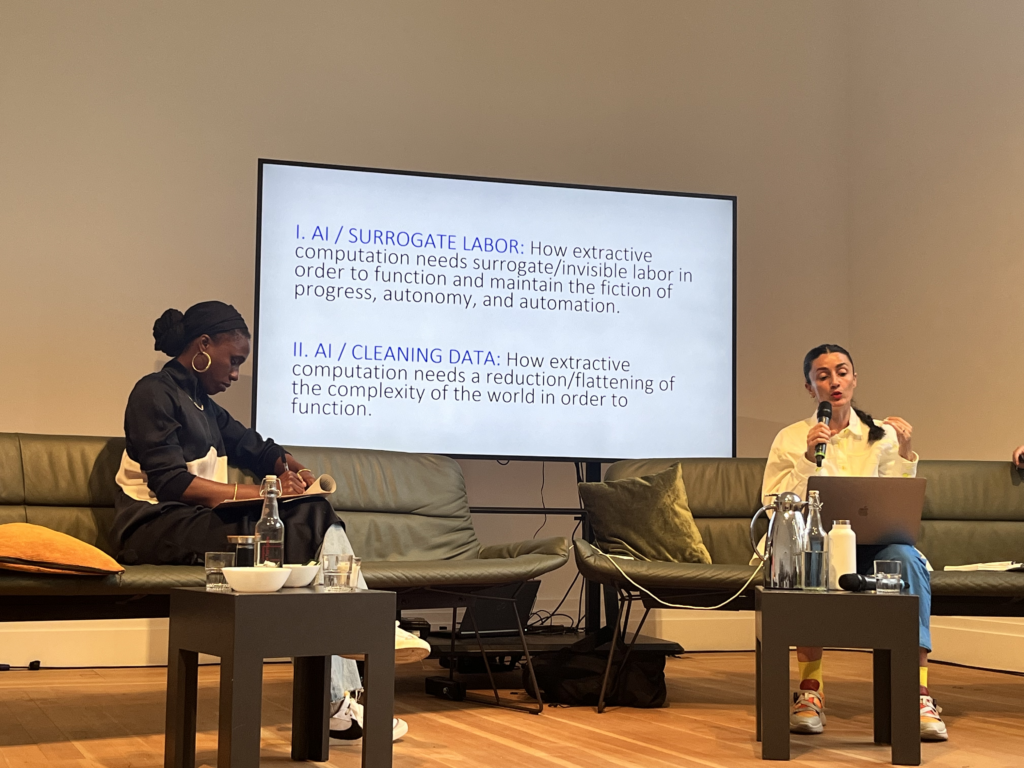

Two weeks later, Missing Data, Cleaning Data, Leaving Data (link) took place at Gropius Bau, an institution that has recently been at the forefront of manifesting postcolonial attitudes. The talks were held as part of Ether’s Bloom: A Programme on Artificial Intelligence and featured presentations and conversations with two of the exhibiting artists, Mimi Ọnụọha and Elisa Giardina Papa. Ether’s Bloom is a program that explores the utopian and poetic possibilities of AI. This talk was one of the events that kicked off the program. Both artists’ work expands on the connectivity of technology. Mimi Onuoha explores the materiality of the internet and references history and colonialism. Elisa Giardina Papa, on the other hand, focuses on the concept of “care,” portraying the labor behind online services and data cleaning from a feminist and ethical perspective. However, it is unclear how Gropius Bau will curate this AI research platform in the future because it is already challenging to imagine discussing utopia. It may have artistic value as an imaginative experiment, but from my perspective as someone who sees that we are colonized by technology and controlled by a small group of entrepreneurs, it appears to be a question that is either long overdue or no longer relevant. I don’t have a clue what the point of exploring this possibility is, but perhaps as the program progresses, there will be other perspectives besides finding artistic value in technology.

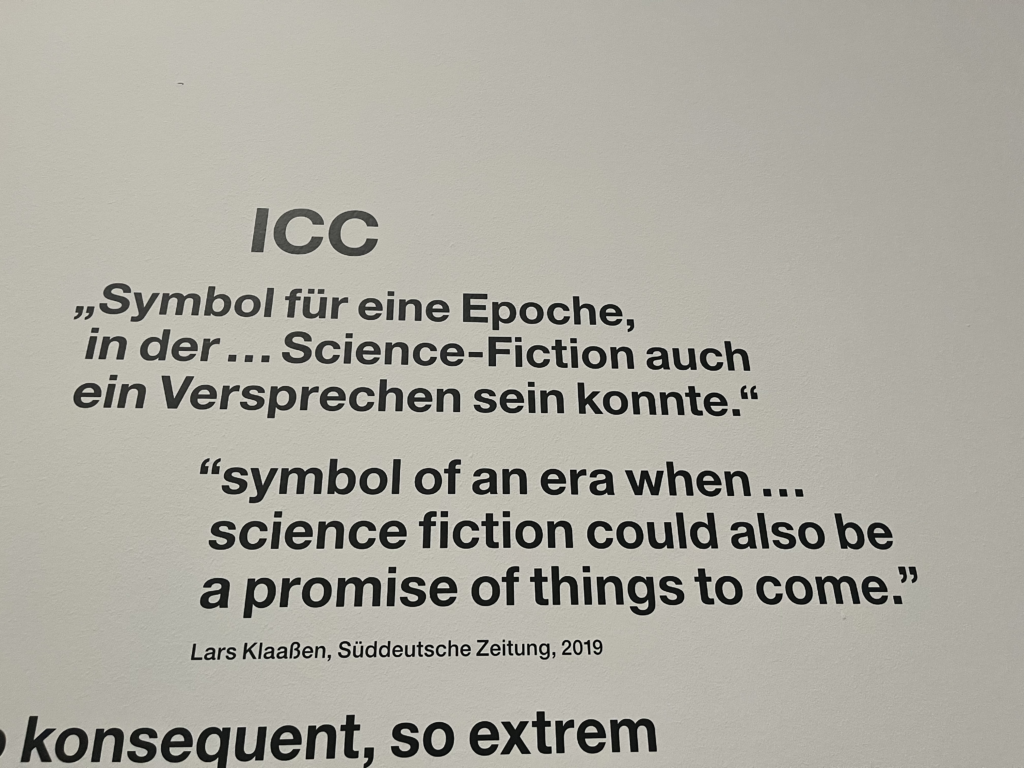

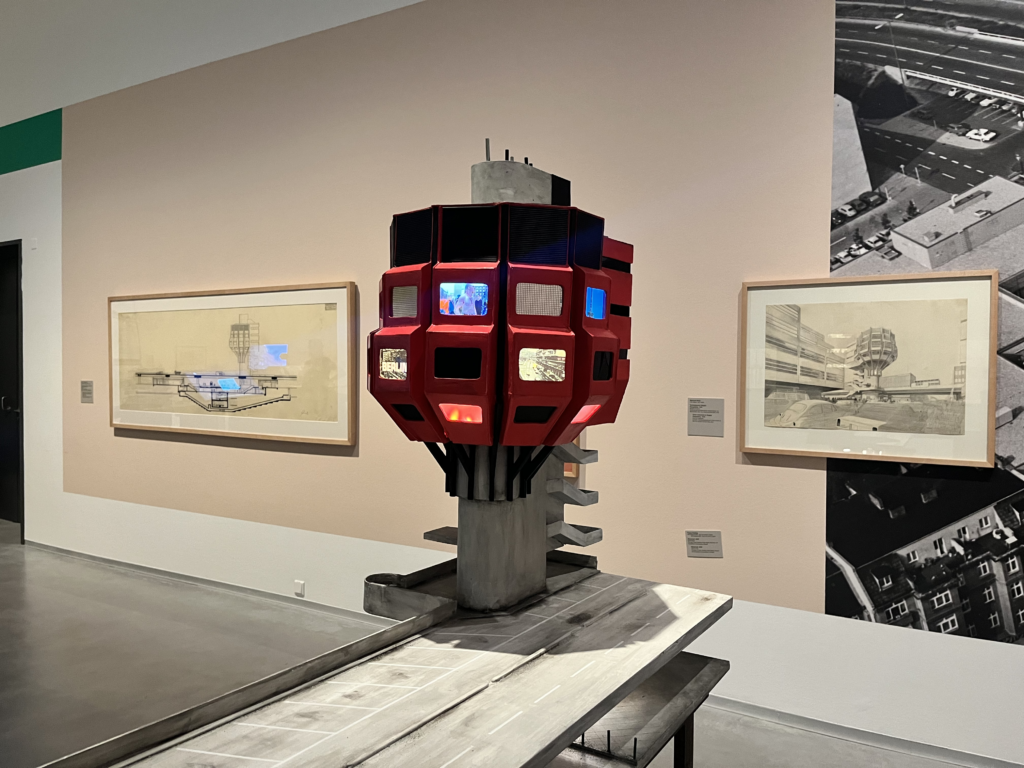

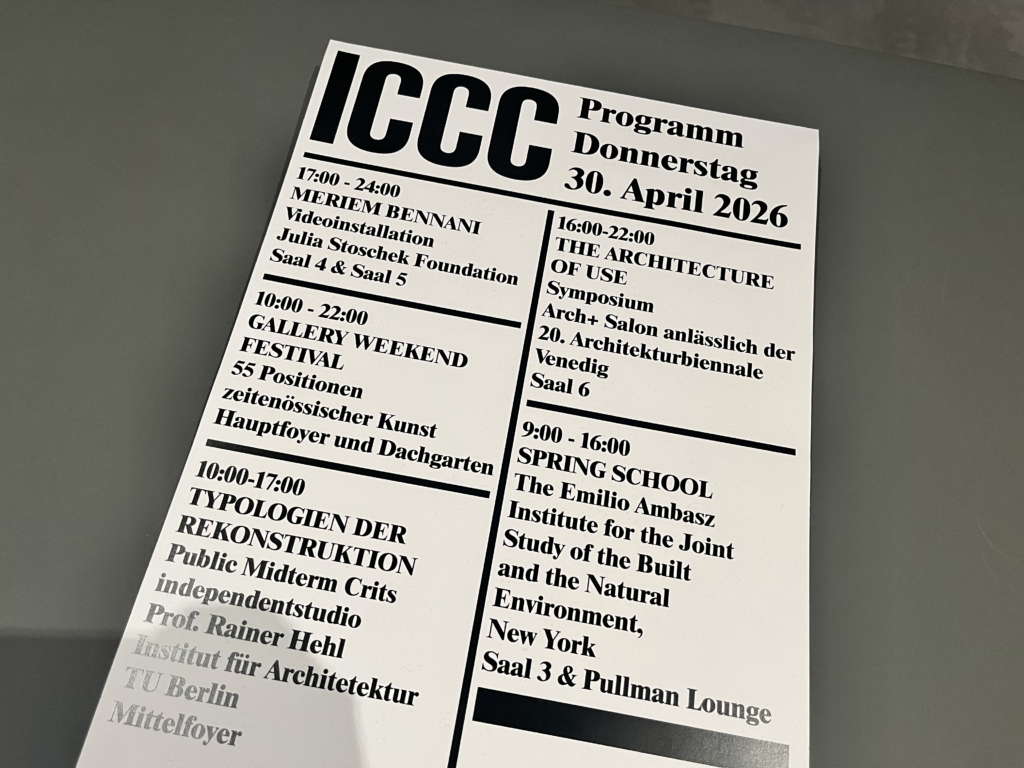

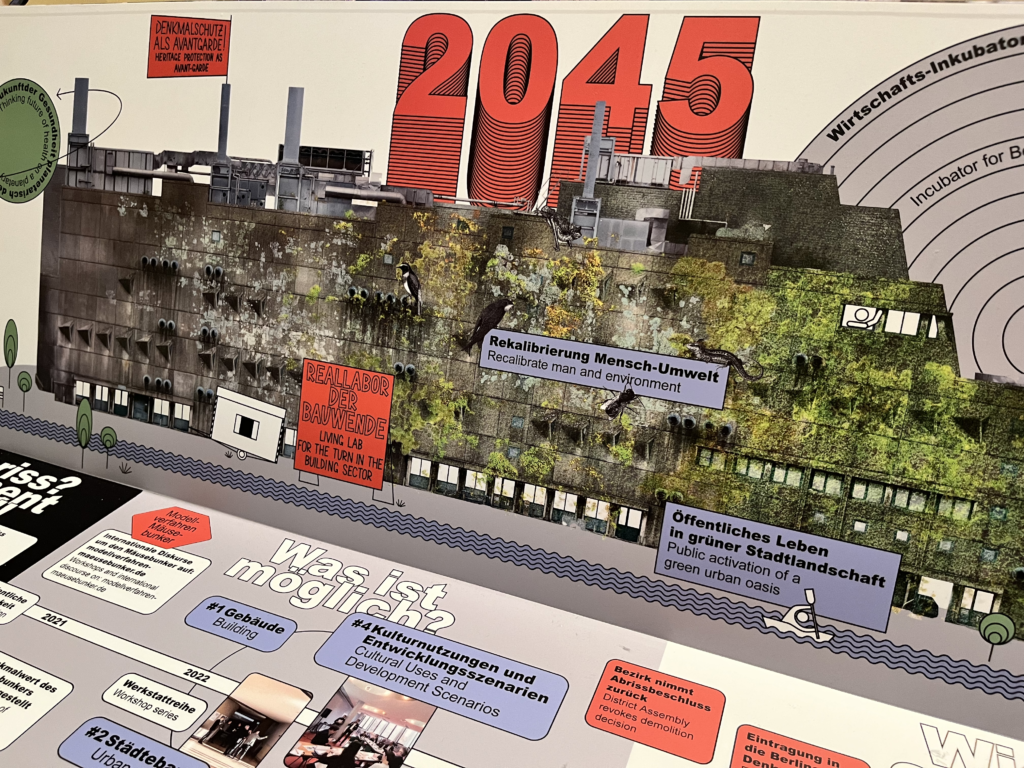

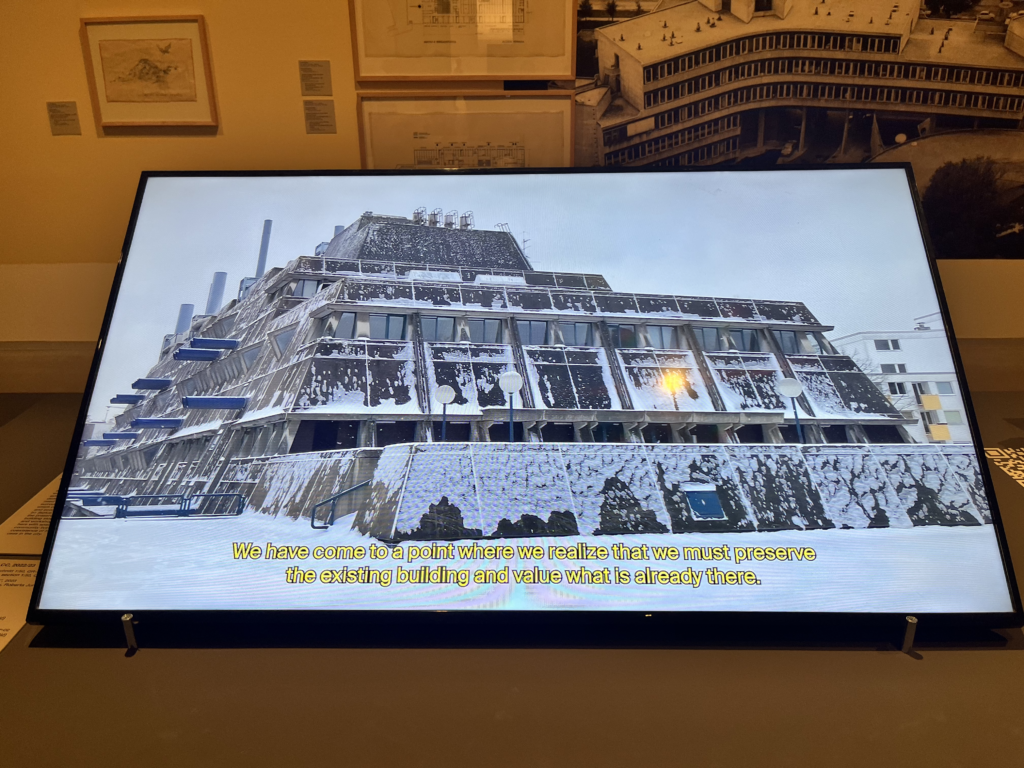

Meanwhile, the exhibition Suddenly Wonderful (link) at the Berlinische Galerie traces the history of West Germany’s buildings from the 70s. At the time, West Germany was showcasing some of the most advanced technology in the world, competing with East Germany and the Soviet Union. As a result, several buildings were constructed as hubs of science, technology, and culture. They reflect the utopia that technology could bring in the most transparent way. The exhibition focuses on three specific buildings: the International Congress Center, the Institute of Hygiene and Microbiology, and the Bierpinsel. Currently, their uses are still a matter of debate, or they remain empty, as they are directly connected to the history of the Cold War and German reunification. The building, which is exceptionally beautiful, appeared like something out of a science fiction movie now and then. However, the difference is that it was futuristic science fiction at that time, whereas now it gives off a sense of science fiction from the past. Beautiful, empty buildings were left behind by an era that believed in new technology and the transformation it could bring. Now, some 30+ years later, they are taxidermized as tangible relics, preserved in time. They will likely be filled in or replaced by another “new” technology, such as AI, to serve as a stage for them or as a reminder of the past. The technology of the past may be lost to nostalgia, which is a shallow resolution that leaves no room for debate about the technology itself.

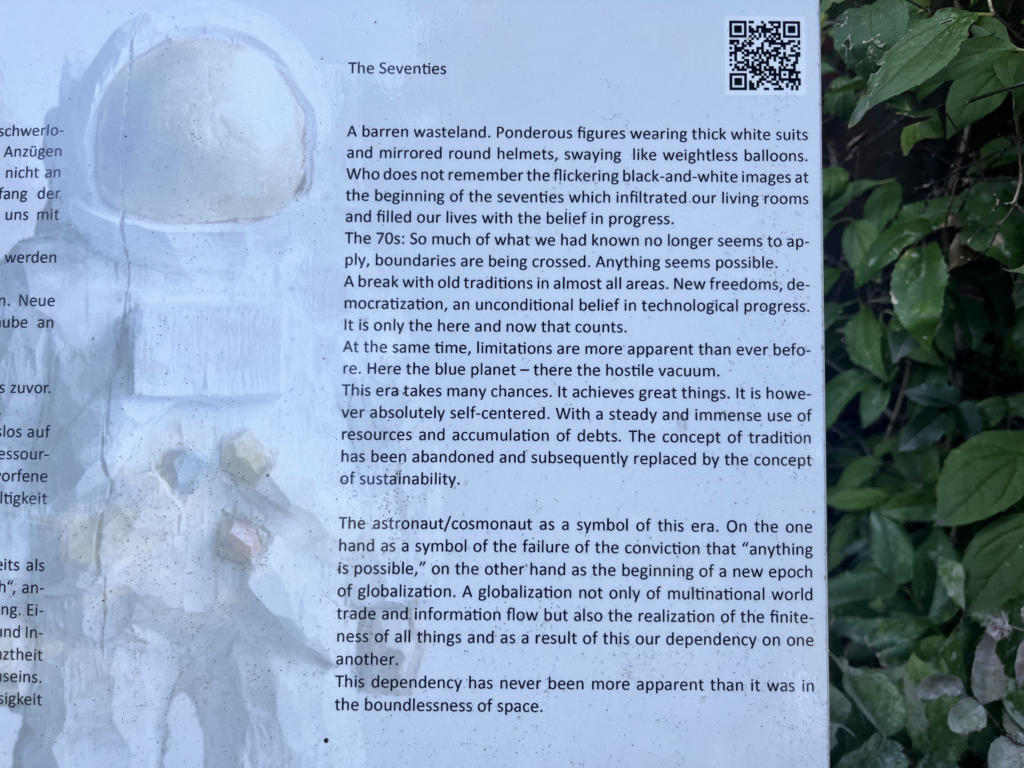

Coincidentally, just outside this museum is a work called Seventies by Albrecht Klink (b. 1962). There is a wooden human figure wearing a space suit with an inscription. “The astronaut/cosmonaut as a symbol of this era. On the one hand as a symbol of the failure of the conviction that “anything is possible,” on the other hand as the beginning of a new epoch of globalization. A globalization not only of multinational world trade and information flow but also the realization of the finiteness of all things and as a result of this our dependency on one another. This dependency has never been more apparent than it was in the boundlessness of space.”

The space technology of the ’70s and the current ambition to colonize space are closely connected, just like the latest West German technology above.

In cities where I don’t know many people, I often turn to Meetup (link). Meetup connects you with people in your city who share similar hobbies. Regardless of the city you’re in, the content remains consistent. It’s all about meeting new people for drinks and conversation, reading a book, or doing yoga. Recently, there have been numerous tech meetups taking place worldwide, aimed at discussing and learning about technologies such as cryptocurrency and AI. Berlin, too, is bustling with these meetups. As I immersed myself in the tech community, posing as a passionate AI enthusiast (which, being Asian, wasn’t difficult), I noticed an interesting contrast. While the art scene in Berlin is known for its enthusiasm in challenging the status quo, particularly in areas like transgenderism, feminism, and decolonization, its focus on technology is more loose and slack than the Meetup events, just like the reminiscent of the 70s.

When these all kinds of ~isms are actively trying to change the way we perceive things by challenging the unchanging history, technology remains superficially present in museums, buried under the glitz of the latest disguise, the emerging cult of AI. Why do technologies in art museums remain so fleetingly enlightening?

If you look closely, these modern technologies are colonized, as I briefly mentioned above, with the majority giving away their data for free while a minority owns it. This is no different from colonialism in the past, so what is happening around the world now can also be seen as AI colonialism. Also, considering how the cutting-edge technology that West Germany proudly showcased 40 years ago is now being utilized in post-colonial cities, I believe that the current colonial technology will also be easily taxidermized and rendered obsolete or replaced with something else. Just like the glamorous buildings of the 70s, I think that the current colonial technology will also be remembered as a troublesome defeat of history.